The History of Brazilian music

Music is a vital part of everyday life in Brazil.

Its cultural richness and its abundant innovation are based on the strong and spectacular racial miscegenation evident in the culture of the country. Its most famous genres are samba, bossa nova and forró. These foundation rhythms are complemented by a contemporary scene, often pushing social demands, such as reggae, funk carioca and rap.

Genres of Brazilian music

Expressing the cultural richness of Brazil

Like most Brazilian cultural activities, music closely reflects the influences of the three main ethnic groups in its society (Native American, Western and African). It transforms into a real blend of sound, which is reinforced by the specificities of each major region of the country to offer a proliferation of genres and interpretations.

While most of its best-known titles are synonymous with “good vibes,” sweetness, and a cheerful atmosphere, they also feature distinctly committed songs. Written in particular under the dictatorship and since the late 1980s, these pieces often denounce social misery and racism in a country with a troubled history.

Innovative music mixing tradition and modernity

The richness of Brazilian music is complemented by an important ability to reinvent itself. This innovation concerns both international genres (jazz fusion, caipira country music…) and popular shows ( bumba-meu-boi …) or more marginal scenes such as rap.

It is also at the origin of several unavoidable sounds of the country, which themselves are quickly transformed into subgenres. Samba is one of the most obvious examples of this permanent evolution. When she appeared at the beginning of the 20th century in Rio, she was inspired by fado and percussion of black African music. But from the 1950s, the softening of its rhythm gave birth to bossa nova.

20 years later, its combination with Caribbean sounds gave birth to samba-reggae, while the use of less noisy instruments gave rise to pagoda.

Have a look at this documentary for a beautiful overview of Brazilian music through time:

Samba, the most Brazilian music

Samba is the most popular music of Brazil and the best known worldwide. Coming from the most modest classes of the suburbs of Rio and punctuated by the drums of its African heritage, its lively character made a success of its melodies on dance floors all over the world. Queen of the Carnival, samba offers an open door to the culture of Brazil.

“Música Popular Brasileira,” a strong identity

The result of the fusion of several traditional genres, the musica popular brasileira (MPB) was born in the mid-1960s. A true expression of cultural differences, it also carries a demand for democracy during a period of dictatorship.

Bossa nova, the sensual Brazilian rhythm

With Bossa Nova, samba becomes “New Wave.” The melodies take a slower, syncopated and refined rhythm, somewhere between cool jazz and classical music, while the whispered song reinforces the poetry of the lyrics.

Contemporary Brazilian music with African roots

Contemporary Brazilian music is distinguished by the extensive variety of its styles and its very rapid turnover. Most of its movements are inspired by the “black” music of the 1970s.

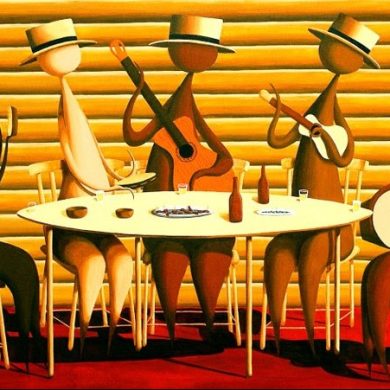

Forró, traditional music and dance from Nordeste

A popular dance originating from the Nordeste, forró music and dancing is emblematic of rural life – often poor – on land scorched by the sun. Long associated with country folklore, it seduces the cities with its sensual choreographies and love songs.