Initially a belief for conventions of intellectuals, spiritism has developed so much in this country that it has become a religion in Brazil that is not only well established, but is recognized as being of public utility.

Relatively recent unlike Catholicism, Protestantism or Candomblé, it has become unavoidable in many areas and is part of Brazilian life. Like the other religions mentioned above, Spiritism was not born in Brazil. Neither did it arrive with the landing of the first settlers or slaves. It took a long detour from the United States and Europe in the second half of the nineteenth century before spreading to South America, and particularly to Brazil. Spiritism is a doctrine based on manifestations and the teachings of spirits. The existence of God and eternal life is fully accepted, accompanied by a concrete communication with various spiritual beings, especially the deceased. What was vaguely called “magnetic phenomena” at the beginning of the 19th century became “American Spiritism” with the arrival of a mission of North American mediums in Europe.

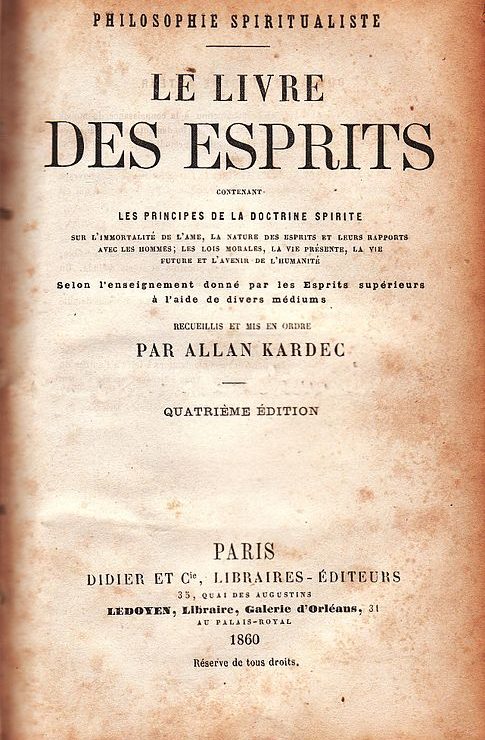

In France, Léon Hippolyte-Denizard Rivail, a schoolteacher from Lyon, better known under the pseudonym of Allan Kardec, took a keen interest when the civil bourgeoisie changed their attitude in the hope of coming into contact with missing beings. He codified the practices, and synthesized his numerous observations in the 1857 book,“The Spirits’ Book”. The name of Kardec quickly became famous and his philosophy was simply called “Spiritism“.

A religion of communication with the spirits

The success of Spiritism from Europe to South America

The success of Spiritism in Europe was overwhelming. Kardec founded the magazine “Spiritist” in 1858, then in the wake of the Parisian Society of Spiritual Studies. The movement spread like wildfire throughout Europe and the doctrine then acquired a social aspect by taking a stand on very avant-garde social issues such as the vote for women, the abolition of the death penalty and pacifism. Exhausted by his travels to Europe where he was going to carry his creed, Allan Kardec died in 1866, giving way to Pierre-Gaëtan Leymarie who maintained the course of the doctrine despite difficulties and attacks of all kinds. The movement reached its peak in the early years of the twentieth century, when the Vatican, frightened by the supernatural aspect, formally forbid Catholics in 1917 to participate in Spiritist sessions. Its impact gradually decreased in Europe, while expanding in South America.

Brazil, on the cutting edge of Spiritism

As early as 1858, the Brazilian elites heard about this new doctrine that engulfed Europe, and the first gathering places appeared in Bahia, then in Rio from 1865. Intellectuals such as Pierre-Gaëtan Leymarie, even corroborated with “Spiritist magazine”. Soon, Spiritist newspapers were introduced in Brazil, and in 1884 the “Federação Espírita Brasileira” (Brazilian Spiritan Federation) was founded. The first director was an influential deputy, Bezerra de Menezes.

After conquering the cities, Spiritism reached the countryside in the early years of the twentieth century, thanks to the roaming of a proselyte of Kardec’s work, Cairbar Schutel. Schutel founded the magazine Revista Internacional do Espiritismo a few years later, alongside writing a number of books and featuring in radio broadcasts. The organisation of free care and the first Spiritist hospitals were down to the work of Schutel.

After the Second World War, Spiritism ran up against the “Umbanda” variant of Candomblé, which was attracting some of the Spiritist practitioners to it. To assert their identity, the Spiritist federations met in Rio de Janeiro in 1949 and signed the Noble Pact (Pacto Áureo) which committed them to remain faithful to the founding doctrine of Allan Kardec. This pact is still in force and gives true meaning to Spiritism in relation to other religions.

Spiritism in Brazil quickly became identified with social action through the opening of libraries and kindergartens. Medium-healers became famous, such as Eurípedes Barsanulfo , José Pedro de Freitas “Zé Arigó” who attracted reporters from all over the world in the post-war years, and the famous Chico Xavier, medium-healer and psychographer, who would write more than 400 books. He was also nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize twice.

Xavier goes so far as to proclaim that Brazil is the “adopted country” of Spiritism, and its third most prominent religion. Some would argue however, that Spiritism is not a religion but a doctrine that is based on principles and not dogmas, and also that the concept of a messiah is absent. Spiritists accuse religion of being a belief held but unverified whereas they “question the real to learn more”. With almost 6 million followers, and 20 million who call themselves “sympathizers”, Spiritism is indeed in third position in the ranking of religions in Brazil.

Public recognition of Spiritism in Brazil

Formerly punished by the law and target of violent attacks, Spiritism has now become a “religion of public utility” in Brazil. It is practiced, at different levels, by all categories of the population, with the exception of the most popular classes who prefer to turn mainly to televangelism or candomblé. Its followers have opened nurseries, hospitals, schools and dispensaries; they work for the improvement of society. Spiritism also helps to cure ailments where traditional medicine has been proven useless, such as the use of exorcisms or curing mental disorders from “another life”. The reception centers continue to multiply throughout the country offering care and legal advice.

Most corporations have a spirit association including magistrates, psychologists, artists, military, and teachers. Spiritism is taught at the Public University of São Paulo and has museums in Curitiba and São Paulo. There are Spiritist television shows and its role in the development of the country was officially recognized when April 18th was dedicated “National Day of Spiritism”.