A potentially sensitive subject depending on what side of the Atlantic one is on, shamanism is a religion fully accepted in Brazil.

Its communities, mainly Santo Daime and União do Vegetal (UDV), are fully integrated with society, and the consumption of Ayahuasca necessary for its practice is no longer a problem in the largest state of South America. This is not always the case elsewhere.

Ayahuasca, a thousand-year-old shamanic tradition in Brazil

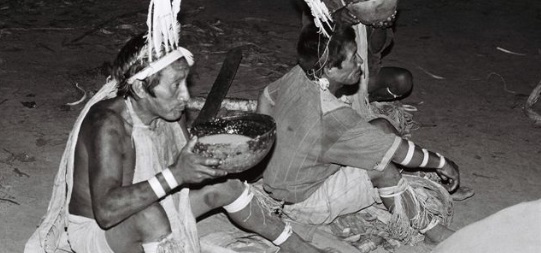

The Santo Daime, like the UDV, draws its roots from the history of the Andean mountains and neighboring countries of Peru, Colombia and Venezuela. The practice settled in Brazil naturally among the natives of the Amazon rainforest thousands of years ago and then amongst the descendants of settlers nestled on the spot. In these religions, priests known as shamans use Ayahuasca (“bitter Liana,” “creeper of the dead” or “creeper-mother” according to interpretations), a hallucinogenic decoction, as sacrament to bring the faithful into a trance during syncretic ceremonies mixing Christianity and pagan rituals.

In addition to its psychoactive properties, Ayahuasca is a potent purgative and emetic to purify the soiled bodies of local natives. It was discovered by Europeans in the middle of the 19th century thanks to an English explorer, Richard Spruce. The study of the texts seems to indicate that Ayahuasca was consumed in the Andes 4000 or 5000 years ago! It was only much later, in the fifties in France, that the chemical composition of Ayahuasca was discovered: it is the association of an alkaloid, the DMT (N-dimethyltryptamine) contained in a local plant, most often chacruna (Psycotria Viridis) with a liana (Banisteriopsis Caapi). This beverage takes as many different names as the regions in which this tradition is practiced, including that of “Caapi”, or Santo Daime, which gave its name to this syncretic religion in Brazil.

Modern Shamanism in Brazil

The Santo Daime in Brazil

The movement was created in 1930 in the Amazon by a former rubber extractor, Raimundo Irineu Serra, who would have met Indian shamans in the twenties and initiated the practice of Ayahuasca as a part of shamanism. Also known as Mestre Irineu, he managed to rally people around him who were from different backgrounds, but united in the celebration of Santo Daime. When he died in 1972, his successor, Sebastião Mota de Melo, founded the “Colônia Cinco Mil” the “daimist” community in Rio Branco in the state of Acre, before returning to the foundations of the movement in the Amazon, where the government entrusted them with the protection of two natural forest reserves. This was a momentous event on the journey to official recognition of the movement.

The use of a hallucinogenic substance in a communion naturally raised questions, especially from the church. Studies were conducted by the Federal Office of Narcotics, the National Anti-Drugs Council and the Ministry of Health, which led to the conclusion that the absorption of Ayahuasca was in no way detrimental to health. Members of the União do Vegetal movement, using the same Ayahuasca beverage, even lent themselves to in-depth studies whose results left no doubt, at least in Brazil, that people who take or have taken Ayahuasca showed positive displays in their daily behavior, especially at the psychological level due to increased confidence, decreased anxiety, and decreased negative psychological symptoms.

The fact that scientists, doctors, psychiatrists and psychologists, are followers of Santo Daime, the UDV and other groups following shamanism lent credit to this research. The fact remains that the Santo Daime was authorized in 1972 (Brazil was still under full dictatorship) and the practice of this religion was consolidated by law in 2010.

A prohibited religious practice in France

The acceptance of the religous practice of shamanism was not to the taste of all governments, especially that of France. Following the requests of French followers to legalize the practice of Santo Daime in France, Ayahuasca was not declared immediately illegal, but an in-depth study of the French health authorities led the government to ban it throughout the country in 2005, simultaneously classifying it permanently on the table of narcotic products. An appeal was dismissed at the very beginning of 2008.

The temptation is therefore great for some to try the experience during a trip to Brazil (or Peru). Even though they were few in amount, cases of fatal overdoses by tourists were reported in recent years. The possibilities of accidents do exist however, for example the consumptions of dangerous concoctions provided by scammers posing as shamans. We can therefore only encourage travelers to be cautious, knowing that this practice is common in the countries aforementioned, and that many testimonies of people who have been well accompanied describe “a contrario” a rewarding experience.