In the 16th century, the Portuguese began the conquest and then the development of the Island of the True Cross, the first name of Brazil.

Considered for a long time as the starting point of the history of Brazil, the colonial era of Brazil is distinguished by the intensive export of raw materials and by a large slave trade. Several economic and institutional advances obtained in the early nineteenth century would eventually lead to the end of the colonial period and call into question the guardianship of Lisbon.

The colonial era of Brazil – at first, a modest colonial act

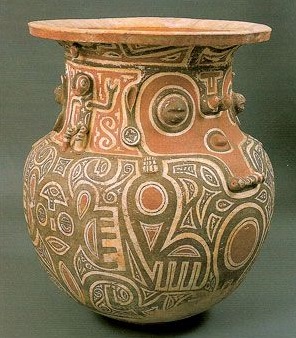

If its coasts were already recognized by navigators such as Columbus, Brazil was officially discovered in 1500 by the explorer Cabral. Under the Treaty of Tordesillas, the territory, then named “Island of the True Cross”, returned to the Portuguese. Despite an enthusiastic description of its resources by the first European visitors, its colonization remained limited. It aimed mostly to send pau-brasil wood to the metropolitan areas, known for its beautiful dye colour of “vermeil.”

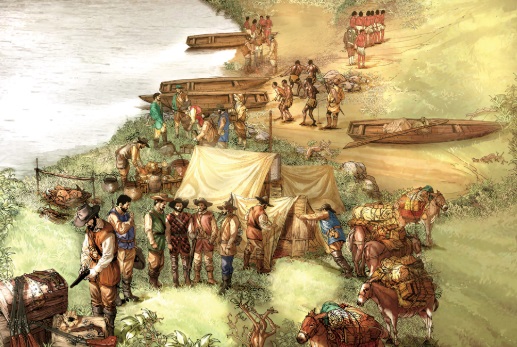

It was the attempts to establish “equinoctial France” (in Guyana) and “Antarctic” (in the Bay of Rio de Janeiro) that accelerated the exploitation of Brazil by the Portuguese Crown. It divided the country into 15 concessions entrusted to captains in 1532. These powerful lords are delegated a portion of the royal rights in the areas of justice, defence, taxation and administration within their new properties. They must also ensure the rapid development of land through the lucrative sugar cane crop.

The 17th century, a flourishing triangular trade era

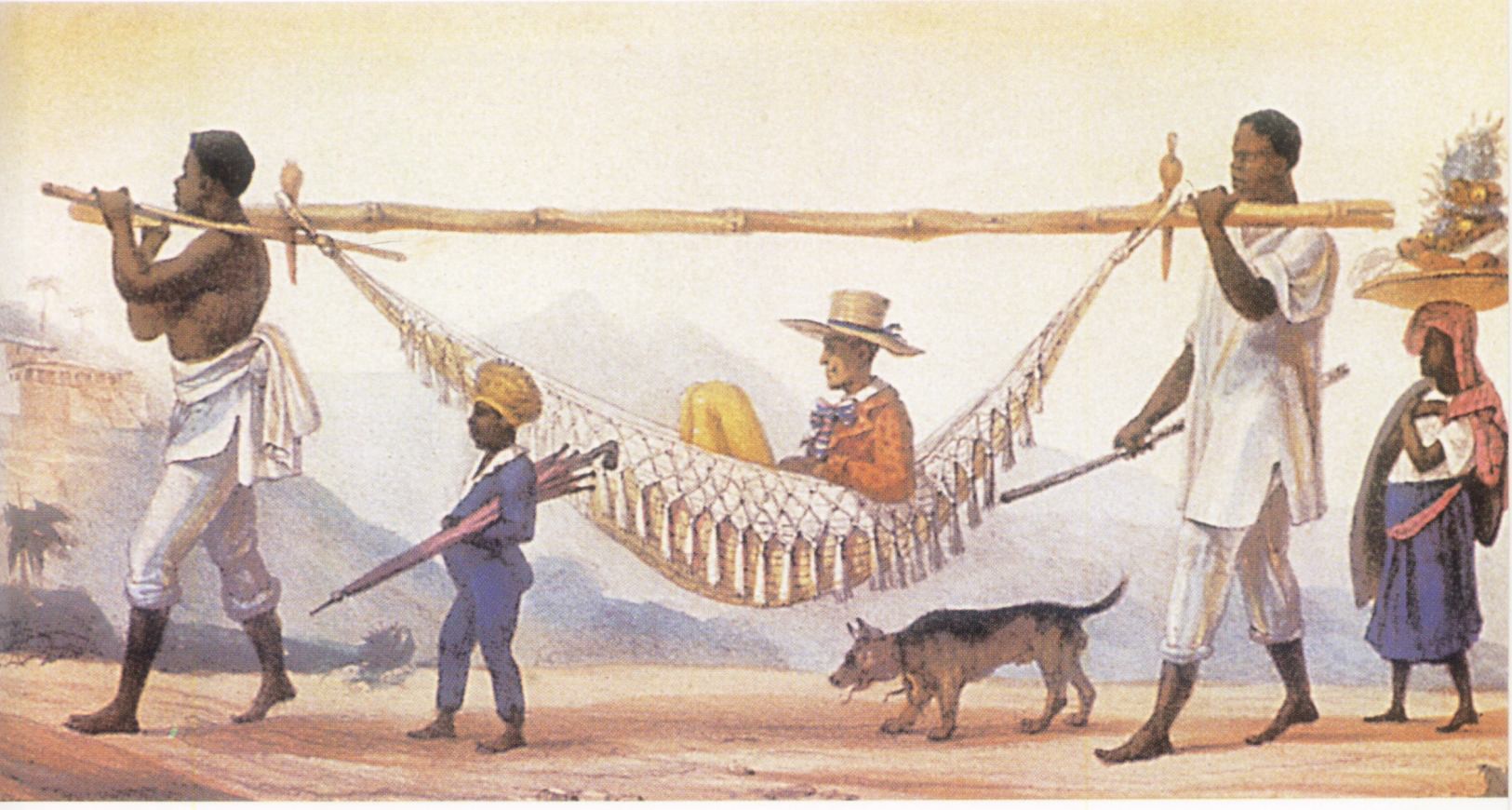

Organized in vast areas, agriculture in the colonial era of Brazil required a large workforce. From 1550, it relied on the massive use of African slaves, whose deportation would fuel a thriving triangular/bilateral trade for more than 300 years. Less than a century after its discovery, Brazil became the world’s largest producer of sugar, increasing its wealth considerably. Its large urban centres, whose cobbled streets often resemble Lisbon, are covered with public buildings with facades decorated with azulejos (white and blue tiles) and elegant palaces. They welcomed the most prosperous settlers, the afidalgados which consisted mostly of aristocracy. This historical period also played a major role in the miscegenation of the country. The scarcity of Western women forced the new owners to take wives (or even mistresses) of African or Native American descent. This resulted in the development of communities of mixed people known as “caboclos.”

Brazil less and less subject to the Crown

During the eighteenth century the production of sugar began to slow down, but the discovery of rich deposits of gold and diamonds in Minas Gerais offered a second economic and demographic boost to the colony. The masterpieces of Baroque religious art from the ancient cities recall the prosperity of the time.

This new period of growth, bolstered by the success of coffee growing, was accompanied by a clear loss of Lisbon’s authority over Brazil. The big landowners orchestrated the local political game, often consolidating their authority with armies of mercenaries, the Bandeirantes.

The autonomist inclinations were accelerated by the temporary emigration of the sovereign of Portugal to Rio following the political upheavals caused by the Napoleonic wars. The colony enjoyed a more favourable status in 1815, becoming a kingdom unified with Portugal. With the declaration of the Carta Regia, it also gained its own institutions (national bank, university, official printing press …) as well as a high level of freedom of trade.

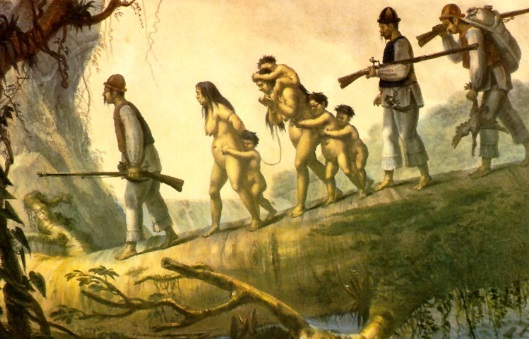

The Amerindians, the first victims of the Portuguese conquest

Estimated to be in the region between 4 to 5 million people upon the arrival of the Portuguese, the Amerindian population soon began to suffer at the hands of colonisation. Beyond the consequences of forced expropriation and slavery, it was decimated by European diseases. In 2010, tribe descendants accounted for about 900,000 people in Brazil.