Regularly in crisis, often threatened with extinction, Brazilian cinema has had its ups and downs. However, taking root in the late nineteenth century, it is an art firmly implanted in the cultural life of the country.

The result of a series of research on the moving image, the cinematograph was invented in 1891 by the American Thomas Edison, and his assistant Laurie Dickson. However, it was the French brothers Louis and Auguste Lumière who really popularized it by offering the first public screenings in 1895.

The birth of cinema in Brazil

The Early days

The news of this scientific, technological and artistic invention was not long in crossing the South Atlantic: a year later, a projection took place in the city of Rio de Janeiro in Brazil, and in 1897, a cinema (Salao from Novidades Paris) opened in the same city. Brazil was positioning itself as a country in full evolution, clearly displaying its desire for modernity, even if it came from Europe or America.

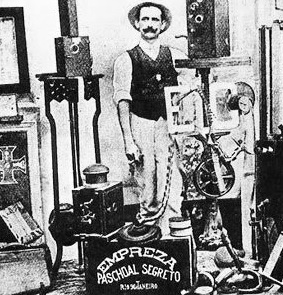

The first officially Brazilian film was shot in 1898 on a boat from the old continent. “Vista da baia da Guanabara” was the work of an Italian immigrant, Alfonso Segreto, but his country of origin was quickly forgotten, and June 19th was declared as “Brazilian Cinema Day”: it was on this date that the film was officially screened in Rio.

Sound, before its time

Soon, film fever would win over the capital of the “Republic of the United States of Brazil”, as it was known in those days (Rio would lose the title of capital in 1960 to the benefit of the newly built Brasilia). From the beginning of the twentieth century, many cinemas opened in the city, mainly projecting fictions from Europe and the United States.

At the same time, a purely Brazilian creative trend was giving birth to what were called “posed films”, rather primitive transpositions of crimes that made the news. The first of them was Os Estranguladores, by Francisco Marzullo, released in 1906, was a great popular success of early Brazilian cinema.

Soon “sung” films began to appear. At that time, of course, there was no technical possibility of sound: actor-singers would be positioned behind the screen to create a live dubbing, to the delight of spectators. Another specificity of the time, was the adaptation to the screen of literary works.

This kind of film also won the favour of the public. However, no matter how popular these movements were, they all contained a major fault that would lead to their detriment: the lack of real fiction, derived from an original scenario. This would quickly be noticed as a major problem by audiences, and was especially noted during the 1910’s with the arrival of North American films.

In the years of ealry Brazilian cinema, the Hollywood industry adopted an aggressive export policy and brought the world its vision of entertainment. The Brazilian public gradually turned away from local productions to succumb to the ancestors of the current “blockbusters”.

From the end of the First World War, distribution networks were created in São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Niteroi, Belo Horizonte and Juiz de Fora to promote the projection of foreign films, the vast majority being American. This came at the expense of early Brazilian cinema, of course.

Customs, to the rescue?

Becoming an omnipotent power, American cinema of the twenties flooded the world market and thus, that of Brazil. The advent of “talking pictures” in 1927 gave Brazil the opportunity to produce its first film, Acabaram-se otários (1929) by Luiz de Barros, but the fight against the American super-power was too unequal. Only a draconian extra-artistic measure could revive the dying national cinema.

In 1930, a law was passed, subjecting North American films to an expensive customs tax!

The measure was relatively effective in the early years, and more than thirty Brazilian films were produced in two years by the newly created production houses. Considered one of the greatest Brazilian directors of the pre-war period, Humberto Mauro took advantage of this movement to realize in 1933 what would be considered his masterpiece, Ganga bruta.

This realistic film, based on the violence of feelings, and imbued with a certain eroticism, however, did not level with the audience and so its author would then turn to the musical, before devoting himself to documentary. This personal story may illustrate the new slump into which Brazilian cinema then entered.

Despite the tariffs, Americans were stepping up their investment in advertising and equipment in Brazil. Most importantly, their thriving cinema with global stars impressed distributors and the public. From then on, the local cinema began to reign in the Hollywood model, with cutesy and tasteless musical productions that definitively turned Brazilians away from cinema.

The second part of the thirties was catastrophic for cinematographic creativity in Brazil. The short lived improvement of the beginning of the decade already seemed so far…

Relapse

During the Second World War, the dark rooms of the country were content with what came from Hollywood and conspicuously sulked at the very rare Brazilian productions. Towards the end of the 1940s, a group of investors and bankers from São Paulo decided to take the bull by the horns and do everything to promote Brazilian cinema abroad.

Beautiful studios were built in Vera Cruz in the state of Bahia, offering state-of-the-art equipment to filmmakers, and pioneers of early Brazilian cinema. These came to “Cinematográfica Vera Cruz” mainly from Europe.

Fifteen Westerns (a genre very popular in the early fifties) would be shot, but distribution problems would be the nail in the coffin of these new creations. Vera Cruz closed in the middle of the fifties, bringing with them the few independent studios that had climbed in their wake.

Meanwhile, another production company, “Atlântida Cinematográfica” specializing in musicals, (“chanchandas“), made those post – war years the heyday of Brazilian cinema. The public appreciated them, and great lyrical artists even sung verses in these productions, but they still faced severe criticism. Once again, the comparison with the level of the Hollywood “musicals” and its huge stars definitely condemned the genre.

At this stage the future for Brazilian cinema looked very dark but these new failures would be the shock to the system needed for the emergence of a new genre that the public and the critics were waiting for, and which would finally obtain international recognition: Cinema Novo.